Antibiotics Are Not Benign

Unnecessary antibiotics for viral infections and incorrect prescriptions for bacterial infections have significant consequences, including increased adverse effects and healthcare expenditures.

Inappropriate antibiotic use is widespread, especially in the outpatient setting. The Joint Commission and Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services required all health care facilities to have an outpatient antimicrobial stewardship program in place by 20201,2 because outpatient antibiotics account for the majority of antibiotic use in the United States.

Reducing inappropriate antimicrobial prescribing from 30% to 20% may reduce antibiotic-associated Clostridioides difficile infections by 17%, with decreased use of penicillins and amoxicillin/clavulanate having the most pronounced effect.3

A group from Washington University School of Medicine recently published their findings on expenditures attributable to inappropriate antibiotic prescribing for respiratory infections in adults. This follows a study they published last year focusing on pediatric patients, which found increased risks of adverse effects and health care expenditures associated with inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions.4

In the present study, the researchers investigated the risks of adverse drug events and related expenditures of patients receiving antibiotics for respiratory tract infections prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. They included medical and pharmacy expenditures in the analyses (eg, presenting to the emergency department for a rash).

Inappropriate antibiotics were defined as prescribing antibiotics to patients with a viral infection or prescribing the incorrect antibiotic or incorrect duration to patients with a bacterial infection. The researchers used MarketScan Research Databases to obtain data based on insurance claims, so only commercially insured patients were included. In addition, they used negative controls to improve their sensitivity analysis; these included ankle sprains and motor vehicle accidents.

Several supplementary tables associated with this study are important for understanding the full picture of the evaluation, including the researchers’ inclusion algorithm and the diagnosis codes (International Classification of Disease) and Current Procedural Terminology/Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes used.

With regard to statistical analysis, the researchers used inverse probability of treatment weights to account for confounding variables in each group. This method can balance the groups in an observational study more so than just propensity matching, in which case sample sizes may end up too small. They included data related to 1.66 million bacterial infections (sinusitis and pharyngitis) and 1.64 million viral respiratory infections (influenza, bronchitis, viral upper respiratory infection [URI], and suppurative otitis media [OM]) captured from 2016 to 2018.

The average age of the cohort was 43 years, more than 50% of patients were female, and almost 50% were from the South. The region is important because data regarding ambulatory antibiotic prescribing from the US show that inappropriate antibiotic prescribing is prominent throughout the Southeast. Consistent with prior research, antibiotics for respiratory infections tend to be prescribed more during winter months than warmer months.5

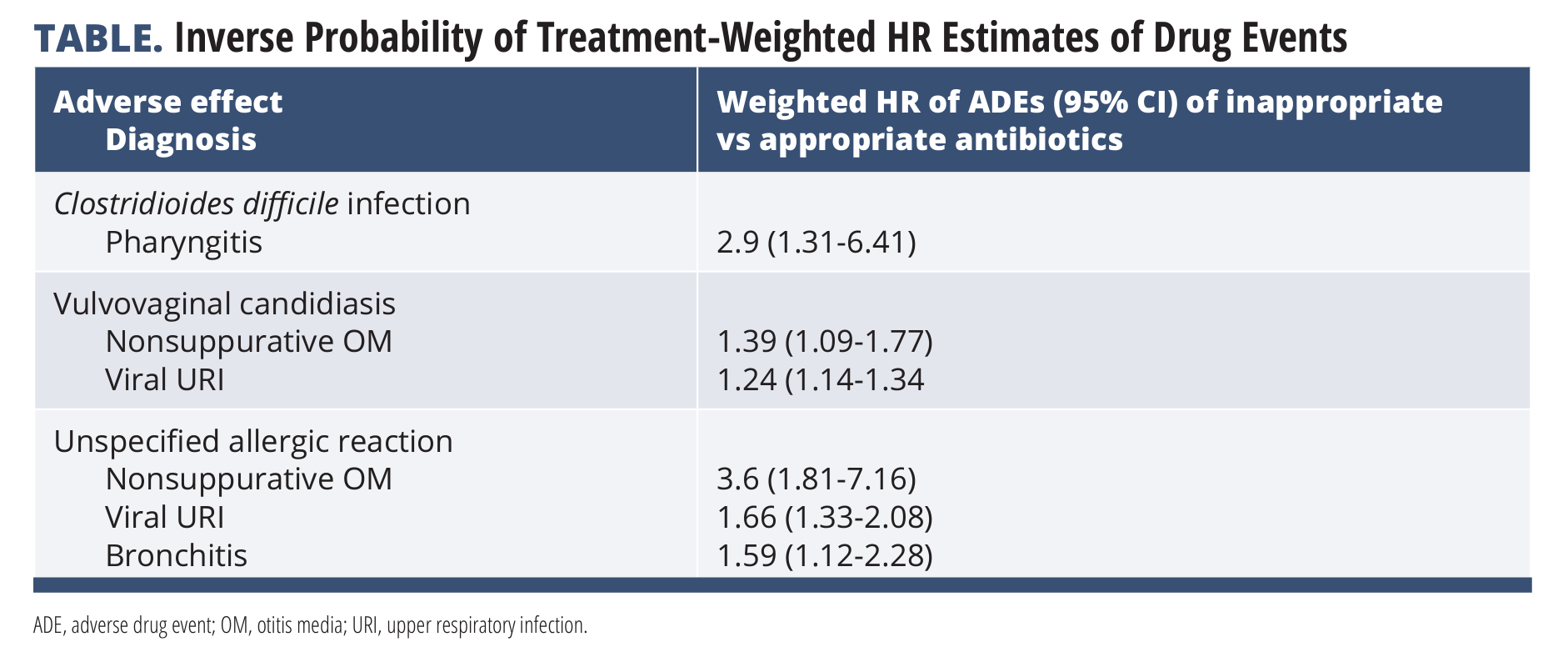

The present study documented types of respiratory infections and percentages of inappropriate antibiotics for each infection type. Bronchitis had the highest percentage of people (66%) who inappropriately received antibiotics. Antibiotic choice also varied by infection type, with penicillin-type antibiotics and azithromycin being common choices for all infection types. Receiving inappropriate antibiotics for pharyngitis was associated with increased rates of adverse drug events in many patients (TABLE).

Inappropriate antibiotics for those with bacterial infections increased the risk of nausea/vomiting/abdominal pain (for pharyngitis and sinusitis), non–C difficile diarrhea (pharyngitis), and C difficile infection (pharyngitis). Inappropriate antibiotics for viral infections increased the risk of vulvovaginal candidiasis (viral URI or nonsuppurative OM) and unspecified allergy (viral URI, nonsuppurative OM, and bronchitis).

The investigators also found high 30-day attributable expenditures for inappropriate antibiotics for bacterial infections and high rates of visits to the emergency department in the pharyngitis group, which contributed to total expenditures. Interestingly, the bronchitis group had fewer subsequent visits to the emergency department, leading to lower 30-day attributable expenditures.

This study reiterates the point that antibiotics are not benign and we shouldn’t be using them “just in case.” Inappropriate antibiotics directly lead to additional health care costs, and increased adverse effects indirectly lead to greater health care resource utilization and medical costs because people may have to visit the emergency department or urgent care.

The authors note that one of the limitations of their study is a lack of knowledge about the providers and whether they commonly recommend or prescribe unnecessary care or medications. In addition, as with many studies that use diagnosis codes to identify patients, if patient diagnoses were miscoded, those patients may not have been captured.

Moreover, because only commercially insured patients were identified, it is unknown whether this information can be extrapolated to uninsured patients who may visit free clinics. The authors also note that they did not account for documented antibiotic allergies, meaning that some of the antibiotics labeled as inappropriate for bacterial infections may have actually been appropriate based on an allergic reaction for guideline-concordant recommendations.

References

1. The Joint Commission. R3 report issue 35: new and revised requirements for antibiotic stewardship. June 20, 2022. Accessed April 3, 2023. https://www.jointcommission.org/standards/r3-report/r3-report-issue-35-new-and-revised-requirements-for-antibiotic-stewardship#.ZCsBLnbMKUl

2. Eudy JL, Pallotta AM, Neuner EA, et al. Antimicrobial stewardship practice in the ambulatory setting from a national cohort. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7(11):ofaa513. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofaa513

3. Dantes R, Mu Y, Hicks LA, et al. Association between outpatient antibiotic prescribing practices and community-associated Clostridium difficile infection. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2015;2(3):ofv113. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofv113

4. Butler AM, Brown DS, Durkin MJ, et al. Association of Inappropriate Outpatient Pediatric Antibiotic Prescriptions With Adverse Drug Events and Health Care Expenditures. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(5):e2214153. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.14153

5. Suda KJ, Hicks LA, Roberts RM, Hunkler RJ, Taylor TH. Trends and seasonal variation in outpatient antibiotic prescription rates in the United States, 2006 to 2010. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(5):2763-2766. doi:10.1128/AAC.02239-13

6. Measuring outpatient antibiotic prescribing. CDC. Updated October 5, 2022. Accessed April 3, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/data/outpatient-prescribing/index.html